The Insights and Story behind TPAMI (2023): False Correlation Reduction for Offline Reinforcement Learning

Published:

this link. Thank you! 😸

Links to our paper:

Code: familyld/SCORE: Author’s implementation of SCORE

I’m delighted to share my paper here. The initial idea for this paper can be traced back to early 2021, the first draft was completed in October 2021, and it was officially accepted by IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence (TPAMI) in October 2023. TPAMI is one of the best and most influential journals in the field of artificial intelligence, with an impact factor of 24.314. From developing the initial idea to its final publication, nearly three years have passed. This experience, despite its challenges, has been quite rewarding. Therefore, besides sharing the contents of our paper, I also want to reflect on the whole process. If my journey can offer you some inspiration, feel free to give it a thumbs up, star our github repo, or cite our paper in your future research. 😉👻 Thank you!

TLDR: High-quality uncertainty estimation + The pessimism principle -> Reliable offline reinforcement learning

The Beginning: A Tale of Pessimism

Back in late 2020, the first year of pandemic, I had just shifted my research focus to the track of reinforcement learning. Following my supervisor’s suggestion, I chose to study the emerging field of offline RL. Sergey Levine’s review paper1 was the first paper I read when I delved into this field. At that time, offline RL wasn’t particularly popular, and there weren’t as many papers available, so each idea was quite novel. From the early SPIBB and BCQ to later ones like BEAR and CQL, we can establish such an intuition: online RL can afford trial-and-error, but offline RL cannot. Therefore, algorithms must try to avoid/suppress queries of out-of-distribution (OOD) actions, as the extrapolation error accumulated in the learning process could lead to failures in offline RL. Based on this intuition, many algorithmic solutions were devised, such as fitting a behavioral policy for regularization or sampling OOD actions and applying additional penalties to the Q-values of these samples. However, did such intuitions genuinely grasp the essence of offline RL?

A meme, credited to Google Research (https://offline-rl.github.io/).

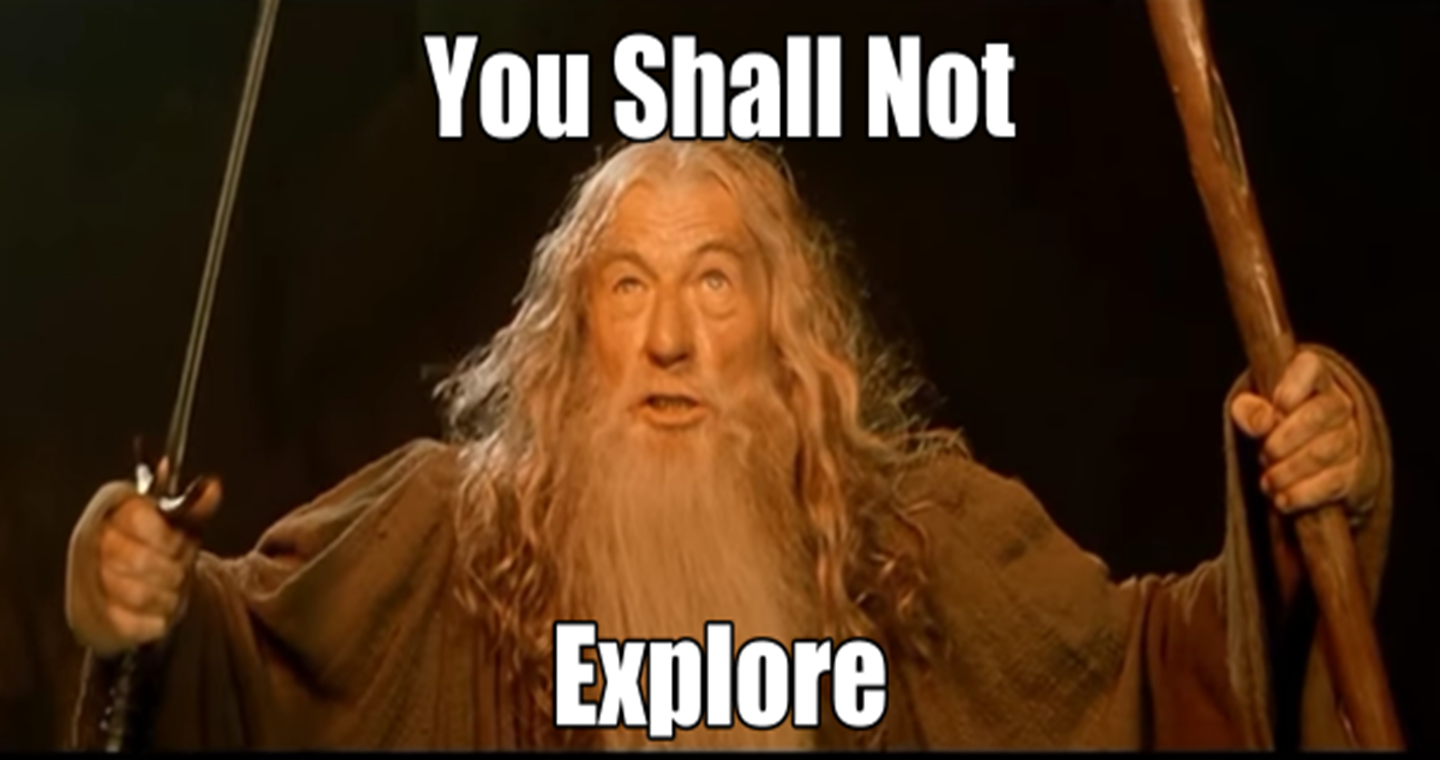

As the last week of December 2020 approached, a paper titled “Is Pessimism Provably Efficient for Offline RL?”2 appeared on arXiv:

At that time, researchers might have been relatively unfamiliar with the term ‘pessimism,’ but those who have studied the exploration problem in reinforcement learning might have some understanding of ‘optimism.’ In online reinforcement learning, optimism is provably efficient. This means that using uncertainty as a bonus to guide the agent’s exploration improves efficiency. Conversely, if we flip the sign (use uncertainty as a penalty), we arrive at ‘pessimism,’ as seen in the title of the paper.

In fact, such a straightforward method is provably efficient in offline reinforcement learning! This conclusion is not only rigorous in mathematical terms but also intuitive and elegant. If we can gather feedback from the environment, embracing uncertainty is a highly efficient strategy. However, when we are unable to collect new information, avoiding uncertainty becomes more critical. It makes so much sense! 😌

How is this conclusion derived mathematically? First, we need to define a metric to evaluate the performance of offline reinforcement learning:

\[\text{SubOpt}(\pi;x) = V^{\pi^*}_1(x) - V^{\pi}_1(x),\]where $V^{\pi^ *}_1(x)$ represents the state value under the optimal policy for the initial state $s_1=x$, while $V^{\pi}_1(x)$ is the state value under the learned policy $\pi$. The difference between the two is termed as “suboptimality.” A larger value indicates a greater deviation of the learned policy from the optimal policy, resulting in poorer performance in offline RL. It can be easily verified that the suboptimality of the optimal policy $\pi^ *$ is zero.

Next, we aim to dissect the core problem of offline RL by decomposing the suboptimality:

\[\begin{split} \text{SubOpt}(\hat{\pi};x) &= V^{\pi^*}_1(x) - V^{\hat{\pi}}_1(x)\\ &= V^{\pi^*}_1(x) - \hat{V}_1(x) + \hat{V}_1(x) - V^{\hat{\pi}}_1(x)\\ &= -\left(\hat{V}_1(x) - V^{\pi^*}_1(x)\right) + \left(\hat{V}_1(x) - V^{\hat{\pi}}_1(x)\right)\\ &= -\left(\sum_{h=1}^H \mathbb{E}_{\pi^*}\left[\langle \hat{Q}_h(s_h, \cdot), \hat{\pi}(\cdot | s_h) - \pi^*(\cdot | s_h) \rangle_\mathcal{A} |s_1=x\right] + \sum_{h=1}^H \mathbb{E}_{\pi^*}\left[ \hat{Q}_h(s_h, a_h) - \left(\mathbb{B}_h \hat{V}_{h+1}\right)\left(s_h,a_h\right) |s_1=x\right] \right)\\ &\ \quad+ \left(\sum_{h=1}^H \mathbb{E}_{\hat{\pi}_h}\left[\langle \hat{Q}_h(s_h, \cdot), \hat{\pi}_h(\cdot | s_h) - \hat{\pi}_h(\cdot | s_h) \rangle_\mathcal{A} |s_1=x\right] + \sum_{h=1}^H \mathbb{E}_{\hat{\pi}_h}\left[ \hat{Q}_h(s_h, a_h) - \left(\mathbb{B}_h \hat{V}_{h+1}\right)\left(s_h,a_h\right) |s_1=x\right] \right)\\ &= \underbrace{- \sum_{h=1}^H \mathbb{E}_{\hat{\pi}_h} \left[\iota_h(s_h,a_h) | s_1=x\right]}_{\text{(i) Spurious Correlation}} + \underbrace{\sum_{h=1}^H \mathbb{E}_{\pi^*} \left[\iota_h(s_h,a_h) | s_1=x\right]}_{\text{(ii) Intrinsic Uncertainty}}\\ &\ \quad+\underbrace{\sum_{h=1}^H \mathbb{E}_{\pi^*}\left[\langle \hat{Q}_h(s_h, \cdot), \pi^*(\cdot | s_h) - \hat{\pi}_h(\cdot | s_h) \rangle_\mathcal{A} |s_1=x\right]}_{\text{(iii) Optimization Error}}. \end{split}\]The third step here leverages the Extended Value Difference Lemma3, and the fourth step makes the expression more concise by introducing the model evaluation error $\iota_h(x,a) = \left(\mathbb{B} _h\hat{V} _{h+1}\right)\left(x,a\right) - \hat{Q} _h(x,a)$. By definition, $\iota_h$ is the error incurred when estimating the Bellman operator $\mathbb{B} _h$ using an offline dataset, quantifying the uncertainty in approximating $\mathbb{B} _h\hat{V} _{h+1}$.

We can see that suboptimality depends on three core factors, but how do we understand them? First, let’s look at optimization error, which is relatively simple. If we directly adopt a greedy policy w.r.t $\hat{Q}_h$, then this term is less than or equal to zero; it does not increase suboptimality. Now, consider intrinsic uncertainty. The paper demonstrates that this term originates from the information-theoretic lower bound and thus is irremovable. Intuitively, this term examines the dataset’s coverage of the optimal trajectory. Without sufficient information, learning the optimal policy $\pi^*$ becomes challenging.

Lastly, let’s focus on spurious correlation. Despite appearing simple, it is crucial in reducing suboptimality. The only difference between it and intrinsic uncertainty is that it calculates the expectation w.r.t the trajectories generated by $\hat{\pi}$ instead of $\pi^*$. This poses a problem: both $\hat{\pi}$ and $\iota$ are dependent on the dataset, leading to a spurious correlation between them. It might be a bit challenging to understand this purely from the formulas, so let’s consider the following example for clarity:

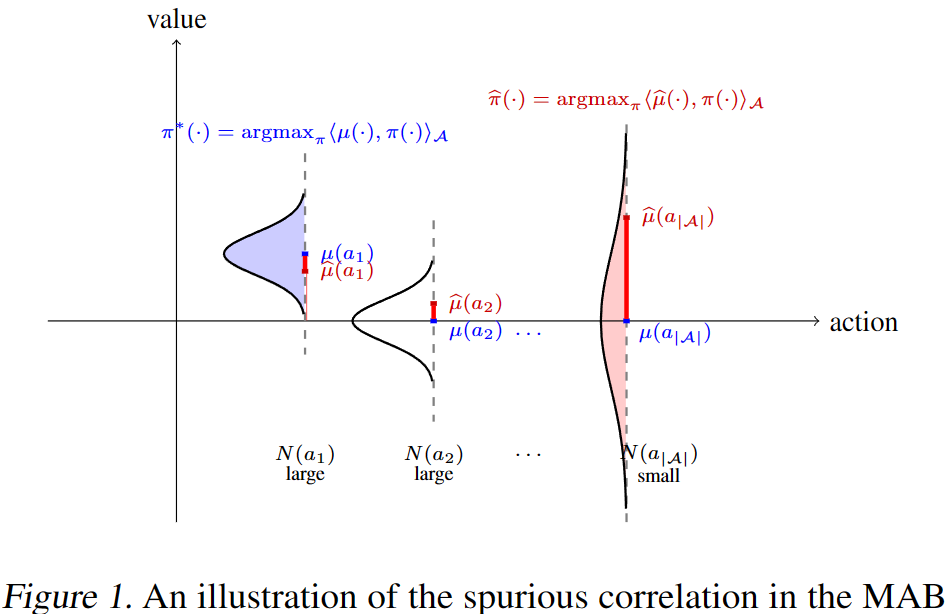

What is presented here is a typical Multi-Armed Bandit (MAB) problem, where there is no need to consider states and state transitions. The horizontal axis represents different actions, while the vertical axis represents the value of these actions. $\mu(a)$ stands for the true value of action $a$, while $\hat{\mu}(a)$ is the sample average estimator following a Gaussian distribution $\mathcal{N}\left(\mu(a), 1/N(a)\right)$. Under this setting, the model evaluation error $\iota(a) = \mu(a) - \hat{\mu}(a)$. It can be observed that when the policy $\hat{\pi}$ greedily selects actions based on $\hat{\mu}(a)$, it ends up choosing actions with over-estimated values due to insufficient knowledge. Hence, we say that $\hat{\pi}$ and $\iota$ spuriously correlate with each other.

Here is a less rigorous example: In some reports, we might see a tendency to highlight a certain entrepreneur’s dropout from school in their youth, as if dropping out contributed to their success in their career. However, the value of this behavior is overestimated, and the strong correlation between dropping out and career success is merely due to a small sample size. Due to such spurious correlations, $\hat{\pi}$ results in significant suboptimality. In sequential decision-making problems, this issue becomes more complicated, as OOD actions are not the only factor to consider. OOD states and in-distribution samples with relatively higher uncertainty also pose similar threats. To enhance the performance of offline RL, we need an effective approach to reduce spurious correlations.

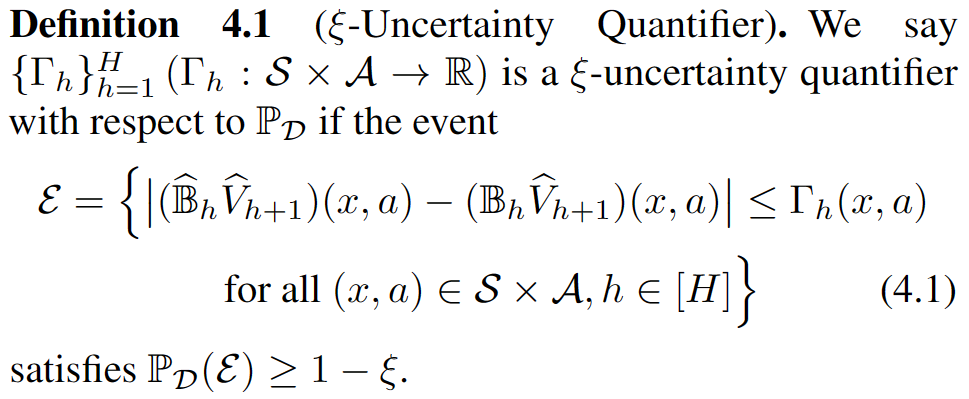

Now it’s time to introduce pessimism. Earlier, we briefly mentioned that pessimism refers to using uncertainty as a penalty. Here, let’s further specify the type of uncertainty we aim to quantify:

To put is precisely, what we need is epistemic uncertainty rather than aleatoric uncertainty. Given perfect knowledge, the former can be reduced to zero, while the latter may not necessarily be zero. By utilizing $\Gamma_h$, we can define a pessimistic Bellman operator:

\[\left(\hat{\mathbb{B}}_h^-\hat{V}_{h+1}\right)\left(x,a\right) \colon = \left(\hat{\mathbb{B}}_h\hat{V}_{h+1}\right)\left(x,a\right) - \Gamma_h(x,a).\]If we approximate $\mathbb{B} _h\hat{V} _{h+1}$ with it, then when event $\mathcal{E}$ occurs, the following inequality holds:

\[0 \leq \iota_h(x,a) = \left(\mathbb{B}_h\hat{V}_{h+1}\right)\left(x,a\right) - \left(\hat{\mathbb{B}}_h^-\hat{V}_{h+1}\right)\left(x,a\right) \leq 2\Gamma_h(x,a).\]At this point, $\iota_h$ is non-negative, hence the contribution of spurious correlation to suboptimality is less than or equal to zero, no longer increasing suboptimality! Meanwhile, we have also obtained an upper bound for suboptimality:

\[\quad \text{SubOpt}(\hat{\pi};x) \leq 2\sum_{h=1}^H \mathbb{E}_{\pi^*} \left[\Gamma_h(s_h,a_h) | s_1=x\right].\]The conclusion is very elegant, as it doesn’t rely on assumptions about the offline dataset $\mathcal{D}$, nor does it constrain the disparity between the final learned policy and the behavioral policy. This means that even if the behavioral policy isn’t optimal and the dataset contains many low-quality trajectories unrelated to the optimal policy, pessimism still ensures that the algorithm effectively utilizes those valuable segments (experimental results on the random and medium datasets in D4RL provide strong evidence).

This paper has deepened my understanding of offline RL while also raising a new question: How to construct a sufficiently “small” uncertainty quantifier that meets the definition, thereby establishing a tight enough suboptimality upper bound? This paper focuses on the linear MDP setting, where it provides an analytical form for $\Gamma_h$ and integrates it into the framework of value iteration. However, implementing the pessimism principle in a more general setting remains a major challenge.

I first came across this paper on social media when it was just released. However, at that time, I was occupied with other experiments, so it wasn’t until around March 2021 that I read through it for the first time. There were certain things that I couldn’t fully comprehend, prompting me to reach out via email to the authors of the paper, namely Ying Jin, Prof. Zhuoran Yang, and Prof. Zhaoran Wang. All three authors graciously answered my questions, and it was this interaction that led to subsequent collaborations.

Hands-on Pessimism

As April approached, we delved into a phase of extensive experimentation after finalizing our collaboration. We aimed to submit to NeurIPS 2021 with a deadline by the end of May, so time was rather tight. However, there was a minor hiccup: a critical bug was identified in D4RL, leading to the release of its v2 version. Some algorithms performed poorly on the updated dataset. To ensure a fair comparison, Yijun Yang and I reran experiments of various baselines using a consistent standard on the v2 dataset. Due to certain algorithms underperforming on the updated version of the dataset, we need to adjust their hyperparameters, which makes time even more pressing.

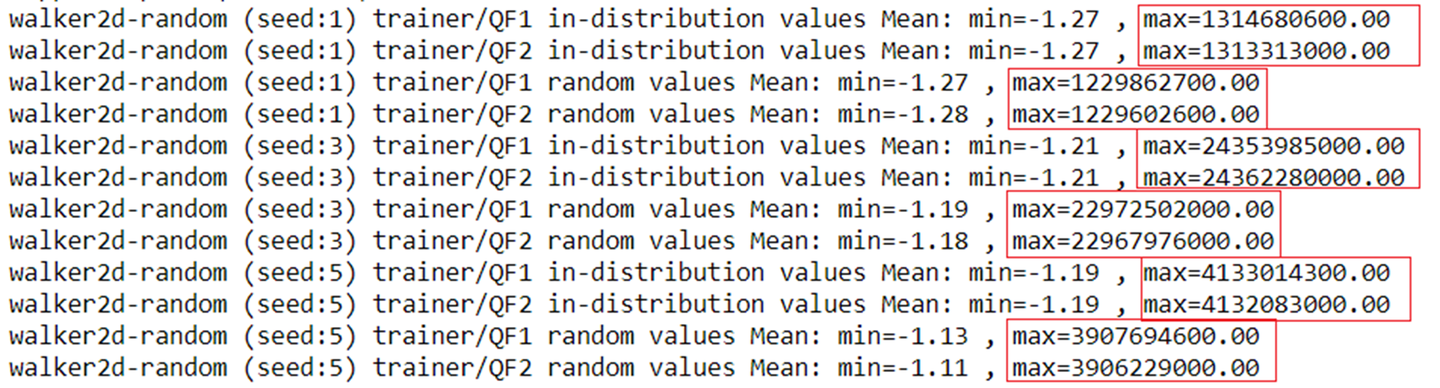

In D4RL-v2, CQL encountered issues with Q-value explosions.

That’s how it went—we worked diligently to reproduce existing methods while designing new algorithms. Simultaneously, we kept a close eye on the latest papers released on arXiv. In fact, later on, we found that most concurrent researches also revolved around the principle of pessimism. However, everyone chose different paths. Some methods were effective in practice but exhibited significant gaps with theory, and we aim to bridge such gaps.

During this period, I had the opportunity to meet Dr. Chenjia Bai and discuss how to implement pessimism together. Chenjia’s OB2I4 maintains a set of critics and effectively estimates epistemic uncertainty through the bootstrapped ensemble method. Based on such techniques, OB2I constructed a UCB-bonus to implement optimism, significantly improving sample efficiency and achieving excellent results in the Atari Games benchmark. Similar approaches can be observed in continuous control problems, as seen in OAC5 and SUNRISE6. Therefore, it seems natural to consider employing a similar method to construct an uncertainty quantifier in offline RL.

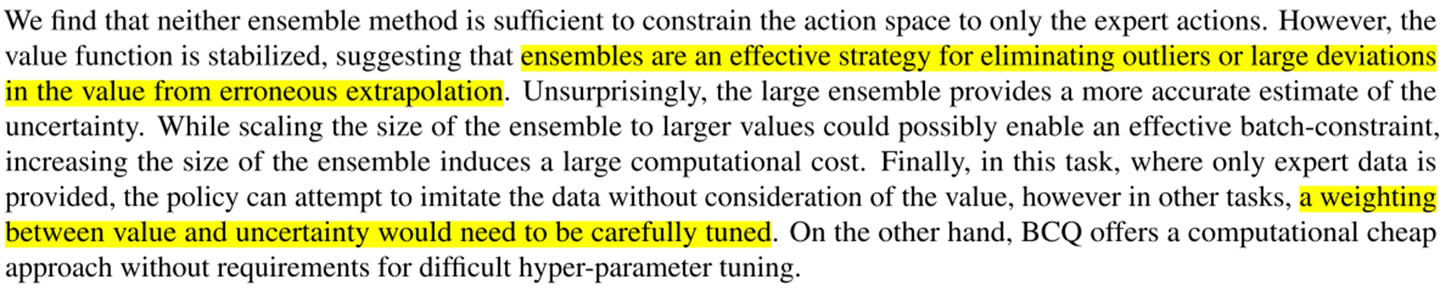

However, in practice, methods based on uncertainty often do not work well. For instance, the appendix of the BCQ paper7 mentions an experiment conducted on an expert dataset. The authors utilized the standard deviation of an ensemble of critic networks to quantify uncertainty, aiming to train the policy network with parameters $\phi$ by minimizing such uncertainty:

\[\phi \leftarrow {\arg\min}_\phi \sum_{(s,a) \in \mathcal{B}} \sigma\left(\{Q_{\theta_i}(s,a)\}_{i=1}^N\right).\]This approach can actually be seen as a policy-constraint method that doesn’t require considering returns. If the uncertainty is accuratly measured, the agent should be able to effectively mimic an expert policy. However, experimental results indicate that this method falls far behind BCQ. The authors explain the experimental results in the following way:

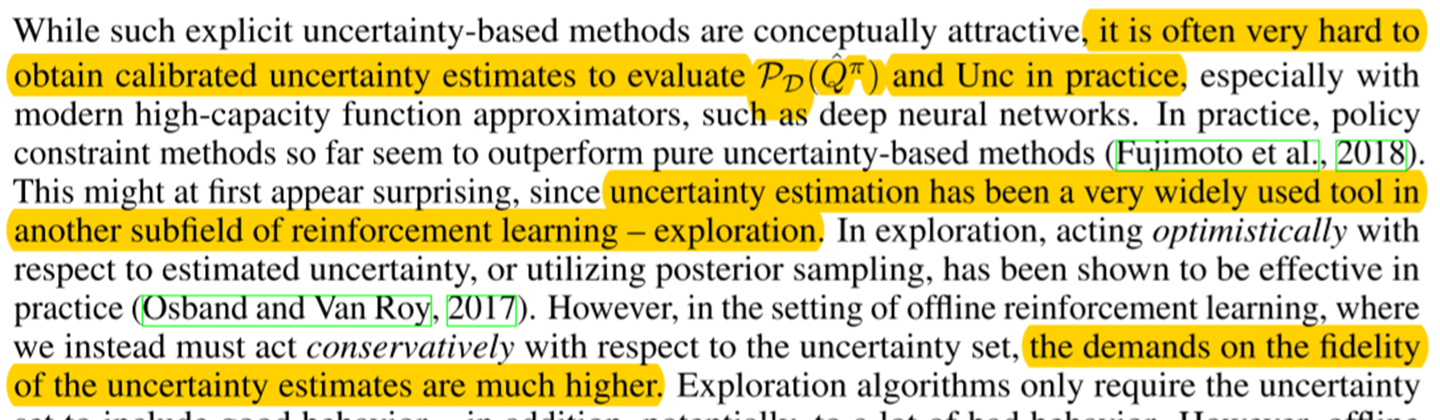

Minimizing uncertainty can stabilize the value function, but it may not sufficiently constrain the action space. When considering settings beyond expert datasets, it’s also crucial to carefully balance the weight of estimated value and uncertainty in policy optimization. In Sergey Levine’s tutorial1, we can see the following discussion:

Earlier, we mentioned that optimism in online RL also utilizes uncertainty. However, in the online setup, trial-and-error is possible, so even if uncertainty estimation is inaccurate, the agent can correct errors by collecting feedback. In contrast, in offline RL, because the agent learns only from a fixed dataset, if uncertainty estimation isn’t accurate enough, the effectiveness will be significantly reduced. High-quality uncertainty estimation is of significance!

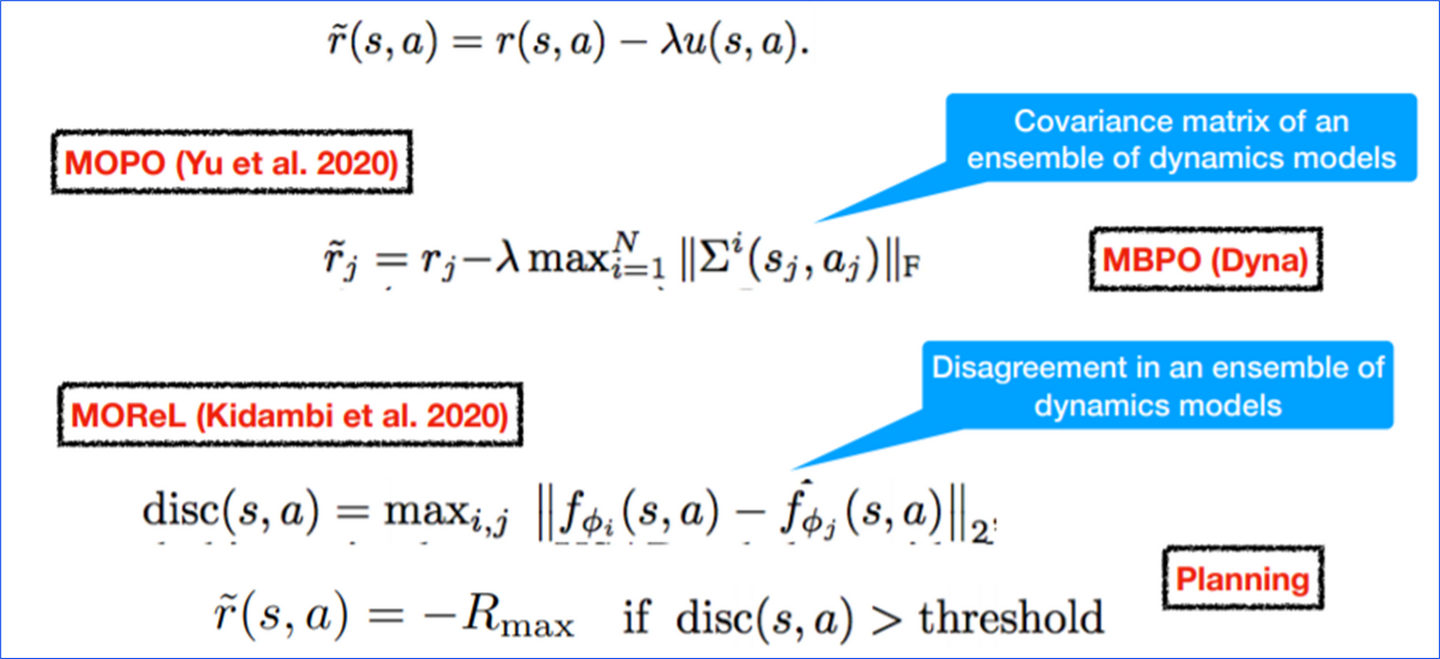

Despite the obstacles facing model-free uncertainty-based methods, model-based uncertainty-based methods have shown promising results, e.g., MOPO8 and MOReL9:

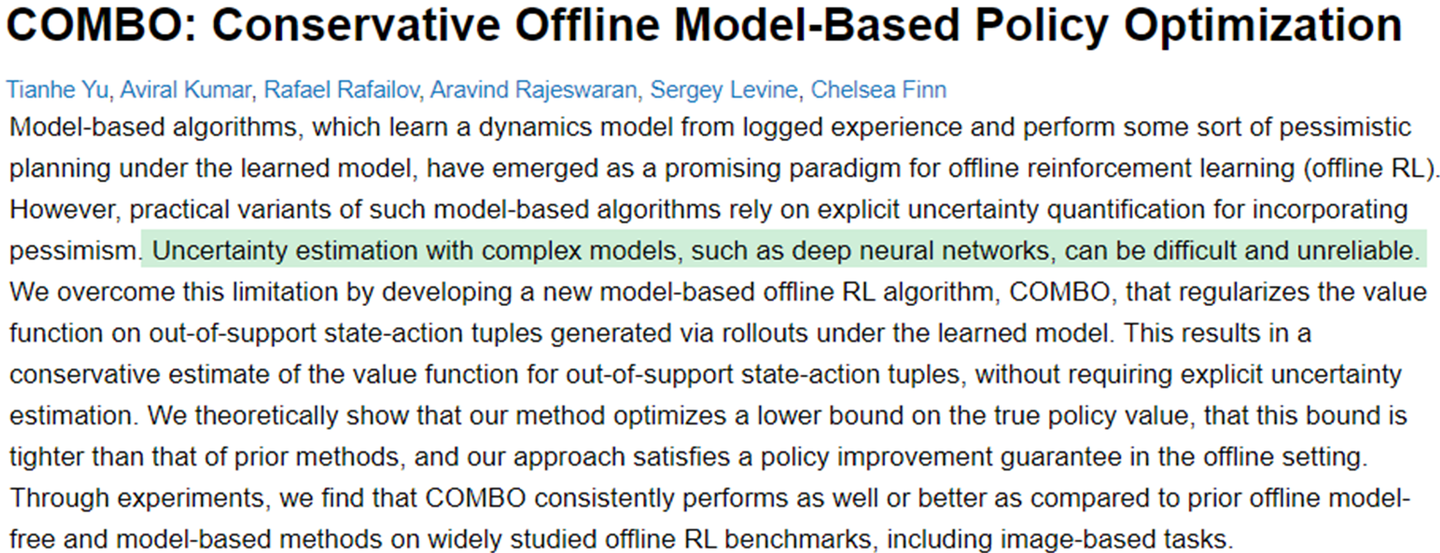

However, in a subsequent research (COMBO)10, the authors of MOPO explicitly pointed out the difficulty in quantifying model-based uncertainty, leading them to abandon the uncertainty-based approach. Instead, they replaced uncertainty penalties with a regularization term similar to CQL. This also confirms the challenges we faced in our experiments - when reproducing MOPO and MOReL, considerable effort was required to obtain reasonable results on the v2 version of the dataset.

Time flies by, with rapid trial and error, analysis, discussions, and another round of trial and error. Despite our efforts to work diligently conducting experiments and analyzing results, we couldn’t produce satisfactory outcomes before the NeurIPS deadline. Nevertheless, this period has allowed us to accumulate valuable experience. For instance, employing uncertainty weighting failed to yield desired results. Those familiar with Offline RL might recall the UWAC11 algorithm proposed by researchers in Apple; however, in our attempts to reproduce the experimental results, we found it heavily reliant on policy constraints, necessitating a combination with BEAR or similar algorithms to obtain strong performance. Furthermore, obtaining uncertainty estimates through dropout does not converge with increasing data, which contradicts the definition of the uncertainty quantifier required by the pessimism principle.

In mid to late June, several interesting papers were released on arXiv. One of them, MILO12, also adopts the principle of pessimism, employing a model-based approach similar to MOReL. It utilizes model disagreement to quantify uncertainty and has shown promising results in offline imitation learning problems. Upon reviewing the code, we discovered that the authors made a small modification to the environment, allowing the agent to observe the velocity in the x-direction, which is a component of the reward and hence crucial for learning the model. This modification might have somewhat simplified the problem. Nevertheless, the experimental results of this paper still strongly support the pessimism theory, demonstrating that pessimism can assist agents effectively utilize expert data.

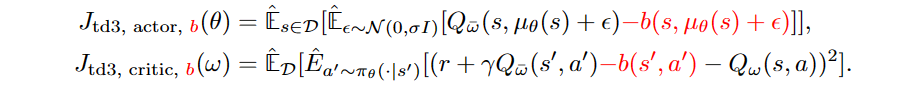

Another paper, contributed by researchers in France, introduces TD3-CVAE in the name of anti-exploration13. This method entails pretraining a Conditional Variational Autoencoder (CVAE), then leveraging prediction errors to construct uncertainty estimates, and used them in the training process of the value function and policy:

Although the paper didn’t have open-source code at the time, its idea was quite concise, so I quickly implemented the code. However, the empirical results were unexpectedly poor; the trained policy completely failed. After carefully inspecting the code, we reached out to the authors of this paper, providing our experimental results and the code. The author compared the codes, but couldn’t identify the issue due to limited familiarity with PyTorch. The two differences — LayerNorm and dividing the bonus by the dimension of the action space — didn’t work after being added to our code. Finally, after a thorough investigation, we found that the core issue lay in propagating uncertainty back during actor’s update! This practice is quite similar to the experiments described in the appendix of the BCQ paper. Allowing to backpropagate the gradients from uncertainty, rather than just having uncertainty as a scalar, introduces a policy constraint in the policy optimization process. This constraint plays a crucial role in the effectiveness of TD3-CVAE, yet it also makes the learned policy dependent on the behavior policy.

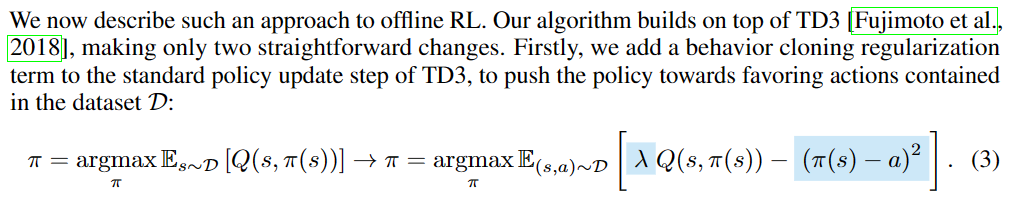

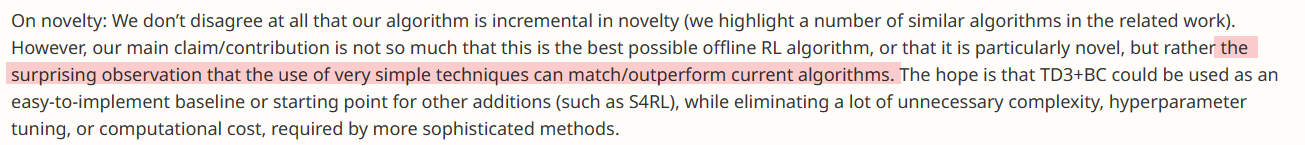

During the same period, Scott Fujimoto, the author of BCQ (and also TD3), introduced TD3-BC14, which established a new state-of-the-art (SoTA) in policy constraint methods. Without the need for pre-training to fit behavioral policies, simply integrating an extremely simple behavior cloning term during policy optimization resulted in remarkably impressive performance. This truly lives up to the name “Minimalist”:

Here’s a summary of the information we’ve gathered so far: ① Model-based uncertainty-based methods are feasible; ② The use of a value regularization method akin to CQL (to suppress the Q-values of out-of-distribution samples) is currently state-of-the-art; ③ Combining model-free uncertainty-based methods with policy constraints is feasible, and BC is a simple yet effective policy-constraint.

Reflecting on this experience, at this point, we chose three distinct paths. Yijun continued along the model-based approach to develop new algorithms, framing the maximization of model returns and minimization of uncertainty as a bi-objective optimization problem, resulting in P315; Dr. Bai explored the approach based on OOD sampling, proposing a model-free algorithm named PBRL16; SCORE, on the other hand, employs behavioral cloning to “warm up” the value and policy functions, aiding the agent in obtaining better uncertainty estimates. While the underlying concepts are quite intuitive and can be easily explained in a single sentence, reaching this point is far from simple.

A Journey Full of Twists and Turns

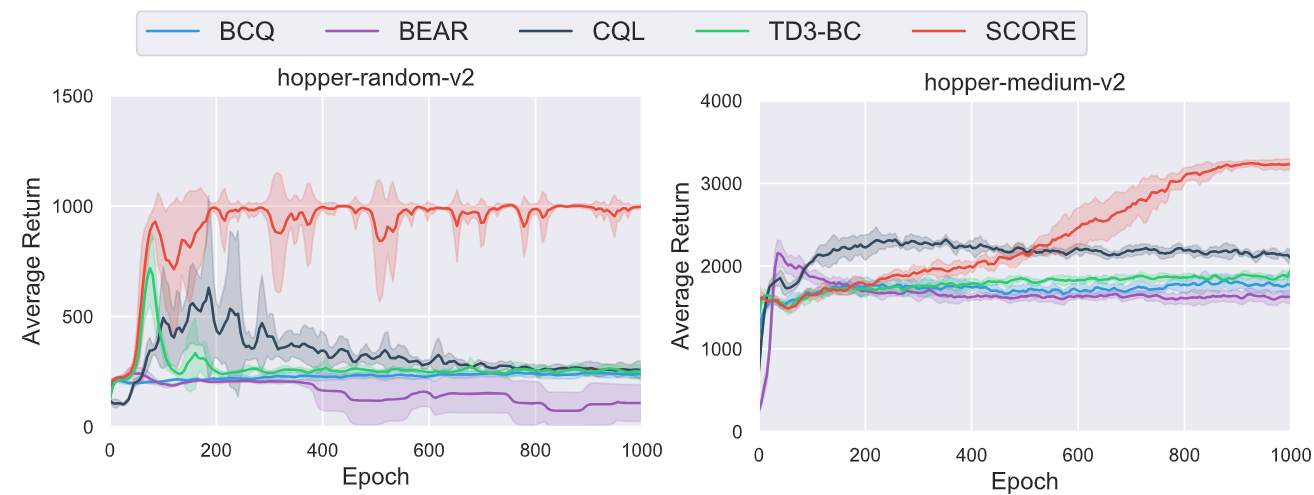

In the latter half of September 2021, we established the theoretical framework corresponding to the designed algorithm and completed the primary experiments. The results were indeed promising; compared to existing algorithms, our method demonstrated comparable, if not superior, performance. Even when applied to random datasets (where the behavioral policy significantly deviates from the optimal policy), SCORE managed to learn fairly effective policies. This indicates that SCORE effectively extracts useful information from the dataset, thereby reducing interference from irrelevant information.

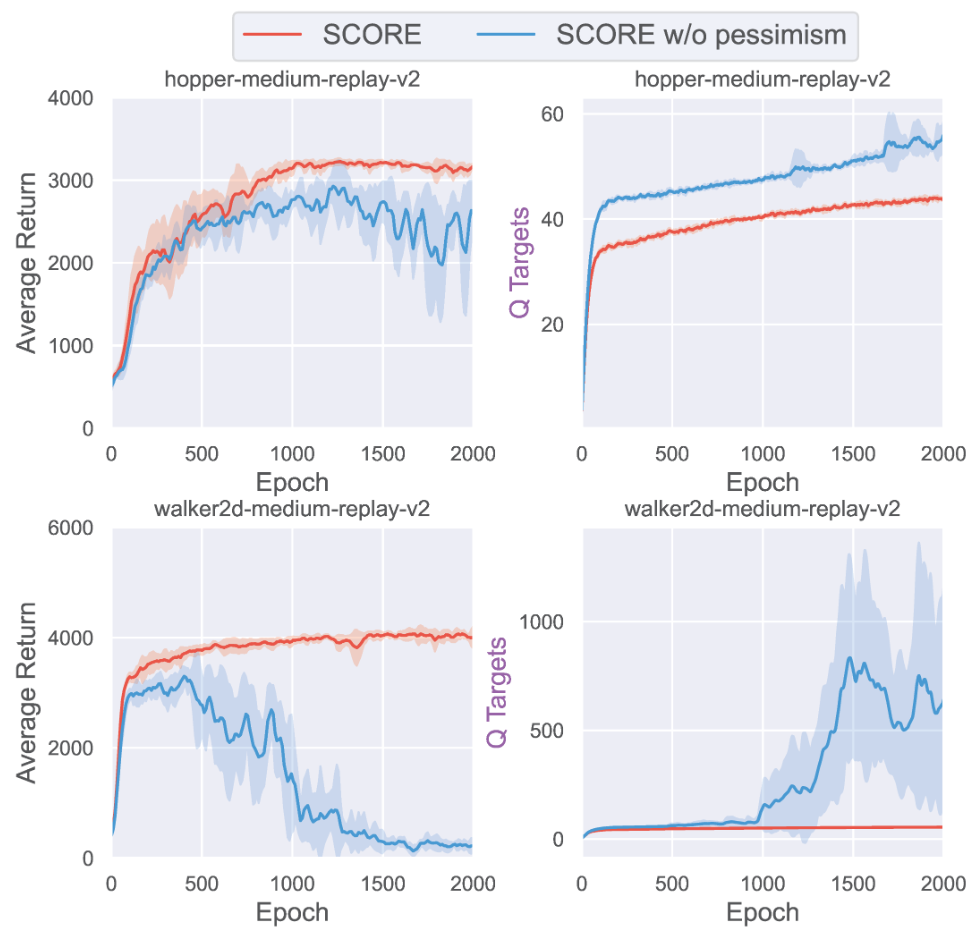

This is a real breakthrough. In practice, behavioral policies are often not optimal, so a good algorithm should “automatically ‘adapt’ to the support of the trajectory induced by $\pi^ *$, even though $\pi^ *$ is unknown a priori.”2 Through conducting ablation experiments, we can obtain more evidence that pessimism eliminates spurious correlations effectively:

Without resorting to pessimism, performance may exhibit greater fluctuations or even significant degradation. Furthermore, by examining the curve of Q-values, we can see that the agent has overestimated the value of the actions it chose.

Despite achieving promising results, unfortunately, we were unable to complete all the ablation studies before the ICLR deadline. Therefore, we decided to first upload the paper to arXiv after completing all experiments and subsequently submit it to ICML 2022. In October 2021, we uploaded the SCORE paper to arXiv. After nearly half a year of effort, we finally made progress and happily shared it on my social network. Although offline RL requires pessimism, in reality, we were all hoping for the pandemic to end soon so we can shake off those pessimistic feelings:

"Cat-centric Supervised Learning."

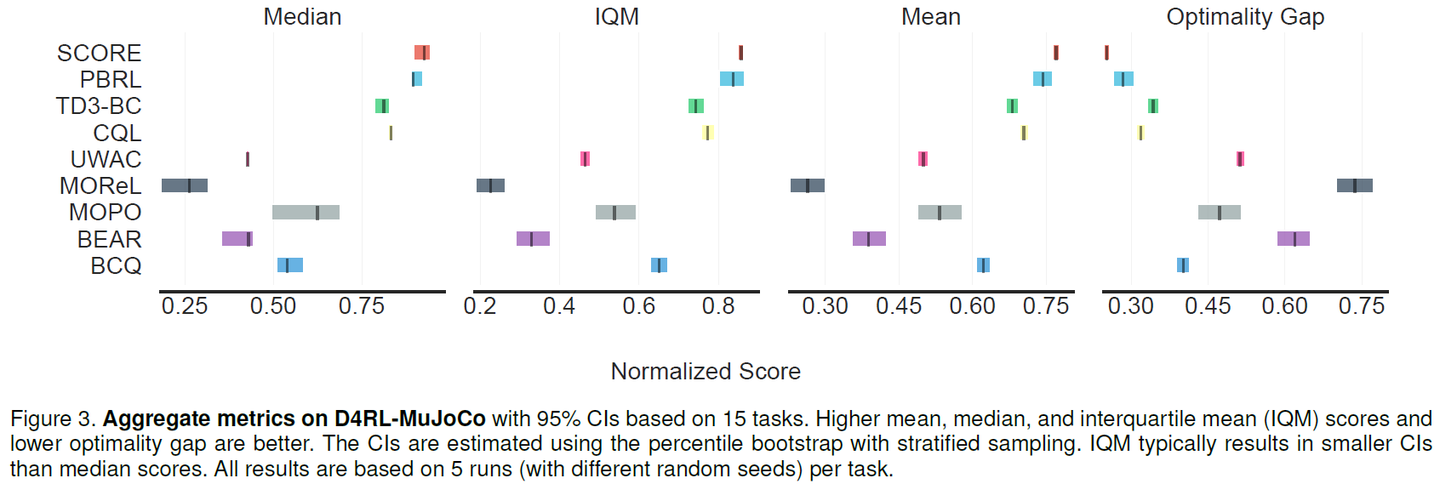

During the rebuttal phase of the PBRL paper, Rishabh Agarwal from Google Brain suggested using the “rliable” toolkit for evaluation. At that time, they had authored a paper (later awarded Outstanding Paper at NeurIPS 2021) focusing on investigating the reliability of RL evaluation results and had open-sourced the “rliable” toolkit. To enhance the reliability of the reported experimental results, we also incorporated this suggestion in our SCORE paper, and the outcomes have been highly promising:

In January 2022, when we officially submitted SCORE to ICML, offline RL had gained significant attention after NeurIPS 2021 and ICLR 2022, firmly establishing itself as a primary research direction within the field of reinforcement learning. Not only did algorithmic research flourish, but applications based on offline RL algorithms also emerged. At this juncture, pessimism had gradually evolved into a sort of “consensus”. Consequently, SCORE encountered a very common issue during the submission process — its novelty was questioned. One of the reviewers commented that the motivation, experiments, and theory in this paper are all very good, but then cited a paper on risk-averse RL to argue that “the novelty of the proposed method is very limited, some related works are missing.” 😵💫 However, apart from this, no other specific feedback was provided.

Despite our best efforts to address the reviewers’ concerns, we received a rejection from ICML 2022. However, throughout this process, we’ve gathered some valuable rebuttal cases worth sharing. For instance, when faced with controversy regarding novelty, the authors of TD3-BC (NeurIPS 2021 Spotlight paper) responded in the following way:

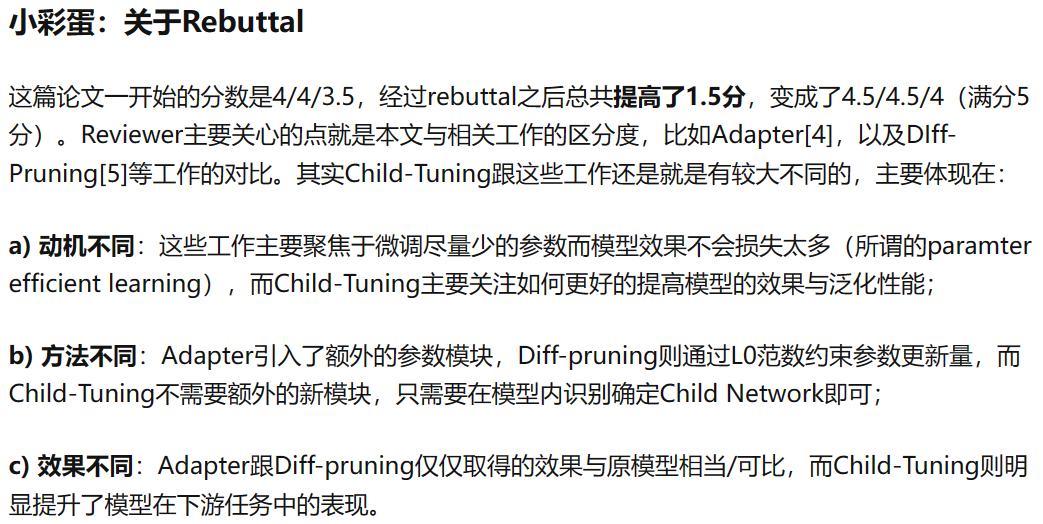

Another example is as follows (taken from a blog post on Zhihu, where the author writes in Chinese):

We genuinely welcome everyone to share their rebuttal techniques and insights!

Despite the disappointment of rejection, I bounced back, revised the paper, and resubmitted it to NeurIPS 2022. The algorithms in Offline RL are evolving rapidly, yet we were committed to developing an approach that adheres to the principles of pessimism theory while remaining simple and effective. In order to complete new comparative and ablation experiments, I pushed through several nights of intense work in a highly tense mental state.

At the end of July, we received the reviews from NeurIPS. There were four reviewers in total, with two giving positive scores and the other two giving negative scores. The main reasons for the negative scores were twofold: novelty and experimental results. Regarding the latter, this is what the reviewers said:

SCORE does not significantly outperform PBRL-prior overall when considering the variance of both methods.

The specific numbers are as follows: SCORE - 77.0±2.0, PBRL-prior - 76.6±2.4, PBRL - 74.4±5.3. PBRL-prior is an upgraded version of PBRL that enhances uncertainty estimation by utilizing a set of random prior networks. However, this approach increases computational overhead. These results were obtained using an ensemble of 10 critics, meaning that each forward pass involves running 20 networks. In contrast, SCORE’s results were achieved using only 5 critics in the ensemble, without the need for random prior networks or out-of-distribution (OOD) sampling (a very time-consuming operation), making it more simple and efficient. Moreover, SCORE has greater advantages over PBRL in theory. It eliminates the need for OOD sampling, thus bypassing the strong assumption of access to the exact OOD target values.

Unfortunately, the reviewers did not respond or revise the scores. By the end of August, we received the rejection notification. The ACsummarized it as follows:

The post-rebuttal reviewer discussion ended in a split recommendation with two reviewers suggesting rejection and two reviewers recommending acceptance. On the rejection side, reviewers remain uncertain about the novelty and contributions of the paper. On the acceptance side, reviewers have pointed out that simple method should be much preferred to complex (and often unnecessary) technical extensions.

The two sides were in opposition, with an average score on the borderline, and ultimately, the AC decided to reject our paper. While facing paper rejection is common in academic research, having our cherished research rejected twice was quite disheartening. Nevertheless, we’ve decided to thoroughly revise the paper and attempt to submit it again. This time, we are determined to submit it to TPAMI.

Submitting to TPAMI was a difficult decision, given that the journal’s reviewing process is much slower than conferences, and a PhD program typically spans only 3 to 4 years. This time, we were fortunate. After a 9-month wait, we received a notification for minor revisions, with each reviewer rating the paper as excellent. We made slight adjustments based on the reviewers’ feedback, emphasizing the differences between SCORE and PBRL (lighter-weight & fewer assumptions) and the theoretical innovation (expanding the conclusions of PEVI from episodic MDP to infinite-horizon regularized MDP and taking policy optimization into consideration). Finally, after submitting the revisions, we were thrilled to receive the news of acceptance after another month and a half of waiting.

Afterword

For those interested in the technical and theoretical details of the paper, please refer directly to the main paper and the appendix. The purpose of this blog post is to reflect on and share the experience. Almost three years have passed. With the end of the pandemic and the acceptance of this paper, it’s time to close the chapter on pessimism and embrace a new beginning. During this period, there were moments when I felt I couldn’t overcome the challenges. I am very grateful for the support of my friends, collaborators, and supervisors. I especially want to thank my wife, who always found ways to help me relax when I was feeling down.

Finally, here’s a little something adorable for my dear readers:

A cute little seal photographed during my trip to the Kangaroo Island.

I hope all your papers can be smoothly accepted, and I wish you all the best in your future endeavors!

A quick advertisement: for those interested in Causal Reinforcement Learning, feel free to reach out! I’m also open to collaborating on new research papers and projects in this field!

Please check Zhihong Deng’s Homepage for further information. Thank you! Enjoy your day~ 😊

References

[2005.01643] Offline Reinforcement Learning: Tutorial, Review, and Perspectives on Open Problems. https://arxiv.org/abs/2005.01643 ↩ ↩2

Is Pessimism Provably Efficient for Offline RL? https://proceedings.mlr.press/v139/jin21e ↩ ↩2

Provably Efficient Exploration in Policy Optimization. https://proceedings.mlr.press/v119/cai20d ↩

Principled Exploration via Optimistic Bootstrapping and Backward Induction. http://proceedings.mlr.press/v139/bai21d.html ↩

Better Exploration with Optimistic Actor Critic. https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2019/hash/a34bacf839b923770b2c360eefa26748-Abstract.html ↩

SUNRISE: A Simple Unified Framework for Ensemble Learning in Deep Reinforcement Learning. https://proceedings.mlr.press/v139/lee21g.html ↩

Off-Policy Deep Reinforcement Learning without Exploration. http://proceedings.mlr.press/v97/fujimoto19a.html ↩

MOPO: Model-based Offline Policy Optimization. https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2020/hash/a322852ce0df73e204b7e67cbbef0d0a-Abstract.html ↩

MOReL: Model-Based Offline Reinforcement Learning. https://papers.nips.cc/paper/2020/hash/f7efa4f864ae9b88d43527f4b14f750f-Abstract.html ↩

COMBO: Conservative Offline Model-Based Policy Optimization. https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2021/hash/f29a179746902e331572c483c45e5086-Abstract.html ↩

Uncertainty Weighted Actor-Critic for Offline Reinforcement Learning. https://proceedings.mlr.press/v139/wu21i.html ↩

Mitigating Covariate Shift in Imitation Learning via Offline Data With Partial Coverage. https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2021/hash/07d5938693cc3903b261e1a3844590ed-Abstract.html ↩

Offline Reinforcement Learning as Anti-exploration. https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/AAAI/article/view/20783 ↩

abA Minimalist Approach to Offline Reinforcement Learning. https://papers.nips.cc/paper/2021/hash/a8166da05c5a094f7dc03724b41886e5-Abstract.html ↩

Pareto Policy Pool for Model-based Offline Reinforcement Learning. https://openreview.net/forum?id=OqcZu8JIIzS ↩

Pessimistic Bootstrapping for Uncertainty-Driven Offline Reinforcement Learning. https://openreview.net/forum?id=Y4cs1Z3HnqL ↩